Bond Pricing in Python with PyO3

Introduction

I recently posted some code that used Rust to calculate the price of a bond (given the yield to maturity) and the yield to maturity of a bond (when given the price). One reason for writing this code in Rust - as opposed to, say, Python - was to create something that’s closer to the type of code one would use in a real pricing system1. But in many cases, it might be useul to write the meatiest code in Rust and then call it from a higher-level language like Python. It’s this scenario that I want to cover here.

It seems that there’s a pretty good system for binding Rust code to Python, in the form of PyO3 and maturin. The Getting Started page of the PyO3 documentation provides a pretty good overview of the steps involved in setting up a project. I followed those steps, and won’t re-hash them here.

I’ve put the repo here: the main Rust code is in src/lib.rs. I won’t copy all the code below, just some relevant changes.

Building with PyO3

Converting the original Rust code into a form usable by Python is pretty straightforward for a basic program like this. After bringing the PyO3 crate into scope by adding use pyo3::prelude::*; at the top of the lib file, we can then use various attributes to tell PyO3 that we’re creating a Python module:

#[pymodule]

fn pyo3_bond_pricing(_py: Python, m: &PyModule) -> PyResult<()> {

m.add_class::<SimpleBond>()?;

Ok(())

}

There are few other changes we have to make, with the exception of adding attributes at some points in the code, so that PyO3 knows we’re treating a piece of code as a part of our python accessible code. The two attributes we use here are the #[pyclass] attribute above the struct we create to represent the bond, and the #[pymethods] attribute above the impl of methods for the struct.

An additional difference from the basic rust code is that we need to give python a wy to construct an instance of the class when we want to do so. This requires adding a new method (with the #[new] attribute before it) to be called when we construct a class instance.

Testing the code

After we’ve taken these steps, and run maturin develop, the library is ready for use! We can create a short .py file to test the basics:

from pyo3_bond_pricing import SimpleBond

bond1 = SimpleBond(1000, 0.04, 2, 10, 0.04584, 0)

bond2 = SimpleBond(1000, 0.04, 2, 10, 0, 953.57)

print(f"bond price is {round(bond1.solve_price(), 2)} USD")

print(

f"bond yield is {round(bond2.solve_yield_to_maturity(0.01, 1000, 0.00001, 0.00000001), 4)}"

)

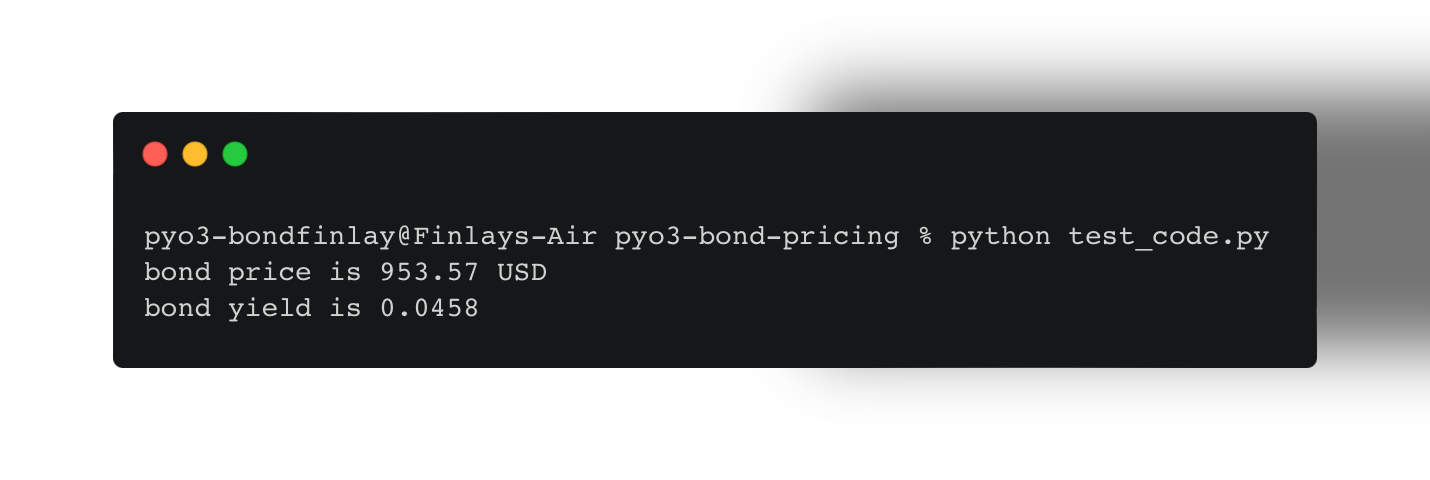

When we run this file in the terminal, we get the following output:

which is what we expect, and matches up with the output of the Rust code we created previously.

Conclusion

While it’s obviously not necessary to use Rust as the engine behind these calculations, there are use cases where Python might not be fast enough and it’s advantageous to use a language like Rust. While Rust is only one of several options, it’s a language that’s getting more mature and I think it’s an interesting choice to explore.

The next steps for this small program is to make it robust - both to computational issues in the yield solver and to errors that can arise from bad inputs. This is an extension I’ll make in the future by exploring the use of Option<T> to accomodate null values for yield or price: Rust doesn’t have a null type and it requires the use of and Option to handle cases where a variable has no value.

As always, I appreciate any corrections or feedback to feedback@finlaymcalpine.com

-

While there’s no question that the speed benefits of a language like Rust are of little use in a simple case like this, it’s an entry point into the general concept of using high-performance languages under the hood. And Rust is an interesting language that’s gaining a lot of traction in the data space, e.g. it’s the engine behind the Polars DataFrame library ↩